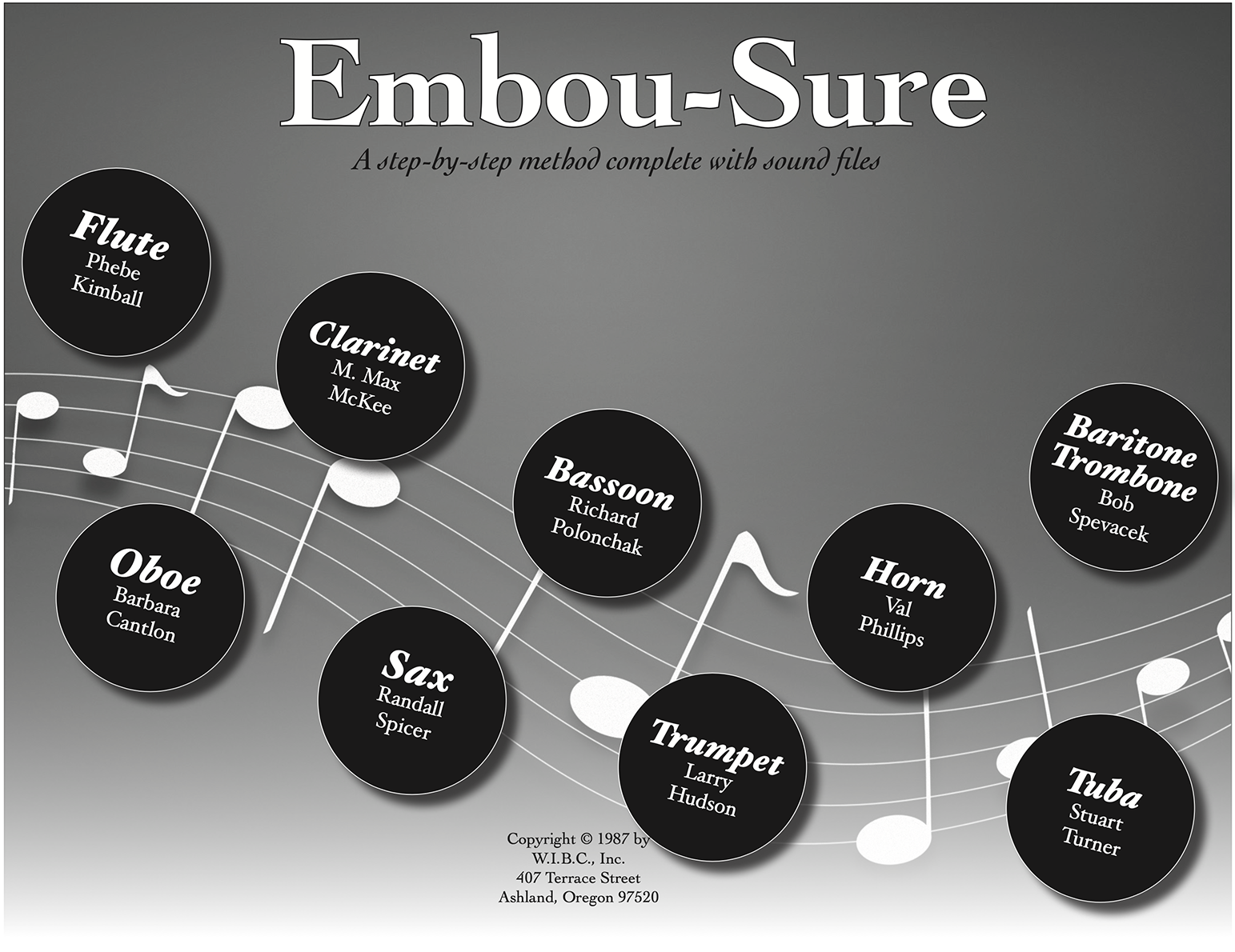

INTRODUCTION

The concept of EMBOU-SURE has been utilized with outstanding success on students of all levels. It is by no means an experimental technique, but rather one that incorporates descriptive terminology as a means of clearly stating the goals, problems, and solutions involved in learning to play the tuba. It is a method that will work equally well for the tuba teacher who is also a tuba player and the non-tuba-playing music teacher.

It had occurred to me, as I am sure it has to many teachers, that specialists in any area have only three advantages over the rest of us:

- Visual expertise in detecting incorrect tone concepts.

- Auditory expertise in detecting incorrect tone concepts.

- Verbal expertise in correcting embouchure formation and tone-concept problems.

So, if we can see, hear, and say EXACTLY the right things, there is no reason that we can’t also be experts in teaching, altering, and refining embouchure and tone. That is, in short, the very intent and purpose of EMBOU-SURE.

And, there’s no magic in all of that either. Simple, very explicit comments during the initial stages of development almost guarantee immediate success. Having applied the methods detailed in this article to the instruction of beginners of all ages (including some as young as six years), I’ve been really amazed by the instant effectiveness of these concepts. It’s very exciting and it’s the reason I decided to join in the development of this series

EMBOU-SURE is formulated on the concept that the prospective instructor has also “taken the course.” It is mandatory that each concept be thoroughly and accurately comprehended. Thus, anyone planning to use this method must start as a beginner, utilizing the text (accompanied by the cassette tape, if possible) as a means of developing a fine sound and an expert teaching system.

PREPARATION

There are two very basic concepts in playing tuba which must be understood by both the tuba student and teacher. These concepts are somewhat unique to the character of the instrument and it is my contention that they should be carefully introduced and discussed prior to the student’s attempts to produce a sound on the tuba. These two concepts have to do with:

1. BREATHING

2. TONGUE PLACEMENT

How often I have heard directors say to students, “more breath support! Blow from your diaphragm!” and each time I hear it, I cringe at the concept that is being conveyed to the student. In fact, the diaphragm muscle has little to do with the breathing process at all and usually ends up being a foe rather than a friend.

The diaphragm is a muscle located just below the lungs at approximately the place where the rib cage ends.

When in a relaxed state, the diaphragm is in a nearly flat or slightly raised position. When the diaphragm is flexed or tightened, it pulls downward. When this takes place, the lungs are also pulled or stretched downward and it becomes a physical impossibility to blow a large QUANTITY of air. By tightening the diaphragm and attempting to blow a large amount of air, we create at the same time an isometric exercise within the body which has no beneficial effect. Try this:

• Hold your hand in front of your face.

• Tighten your diaphragm.

• Try to blow a large quantity of air on your hand.

Doesn’t work, does it? Now relax your stomach and diaphragm muscles and repeat the process of blowing a large quantity of air on your hand. It is really quite easy to do. The tuba player needs to put large quantities of air through the horn because of the size of the instrument itself. The easiest way to accomplish this is to use little or no “diaphragm support.”

“For tuba players, strength is our weakness!” – Arnold Jacobs

A saying which Arnold Jacobs uses frequently is: “For tuba players, strength is our weakness!” That statement pretty well says it as far as the concept of breathing goes for the tuba player.

TONGUE PLACEMENT

The second concept mentioned above is that of tongue placement; once again we have a situation that is unique to the tuba. As previously stated, we need a large quantity of air to produce a good sound on the tuba. The tongue is often the culprit which prevents this process from taking place efficiently.

If you say the syllable “TEE,” you will notice that the tongue is arched up in the back. . .nearly to the point of touching the roof of the mouth. When this happens, we have a block (the tongue) thrown up in the way of the air stream. The result is a restricted amount of air passing beyond that blockage to the lips and an absence of a good tone on the tuba. Remember: the large quantity of air produced through proper breathing does no good at all until it passes through the lips to make them vibrate; if the air is stopped or partially blocked off in the process of blowing, the result will be totally unsatisfactory.

Say the vowel sound “OH” and notice the position of the tongue. The production of the “OH” sound causes the tongue to lay down flat in the bottom of the mouth, thereby causing no obstruction to the air stream. This is the ideal placement of the tongue for ALL RANGES in tuba playing. The “AH” sound will also cause the tongue to rest in the correct position, but if exaggerated, gagging results; once again the throat is closed off. For this reason, the “OH” sound is preferable.

I should also mention here that tongue placement in beginning a note with the tongue, we simply say, “TOH.” When we say this sound, the tip of the tongue hits behind the top front teeth. Never allow a student to the tongue through the teeth as it always causes a sloppy, thick attack. I have heard teachers describe the act by telling the student to “spit out a seed.” Nothing could be further from the correct method of tonguing. Simply tell the student to say “TOH.”

With a basic understanding of these two concepts, we are now ready to move to the tuba itself and prepare to play the first note.

FORMING THE EMBOUCHURE

If possible have an embouchure visualizer or mouthpiece ring available to aid in forming the embouchure. This will make it easy for you to see what is taking place inside the mouthpiece area. Ask the student to place the mouthpiece ring on his lips and say, “OH” and then gradually change to an “OO” sound. This will form the lips into the correct position.

Now have the student grasp a small tube or pen (about 1/8″ in diameter) in the center of the lips. This will cause the lips to tighten toward a central point and will also bring the corners of the mouth to a firm set.

Remember: “OH-OO-SQUEEZE THE TUBE WITH THE LIPS.” Once you have gone through this procedure carefully, the student is ready to make the first sound on the tuba.

THE FIRST TONE

Ask the student to take a deep breath, completely filling the lungs with air. This sounds awfully basic in nature, but it is amazing to me how many students prepare to play tuba by taking a very quick, shallow breath. . .air can not be blown out which has not first been taken in.

So, have the student gulp air with the same feeling in the throat as when yawning. This opens the throat and permits the student to take in large quantities of air in a very short period of time. There should not be a hissing sound as the student inhales, for this indicates that the tongue is arched up near the roof of the mouth. Furthermore, if the tongue is arched during inhalation, it will likely remain there during exhalation.

Now ask the student to put the tuba in position with the mouthpiece near the lips. With the young student, instruct him to place the mouthpiece so that half is on the top lip and the other half on the bottom lip. This is not the most desirable mouthpiece position but about all that will be physically possible with small children. Ideally, the mouthpiece placement should be 2/3 on the top lip and 1/3 on the bottom lip.

Now, take a deep breath, re-form the embouchure (“OH-OO-SQUEEZE THE TUBE”), and blow, expelling the air as rapidly as possible.

#1 – CORRECT RESULT More often than not a reasonable tone will result. The particular note produced is not important at this point. The student will generally produce a second line B-flat or the F directly below the staff. Let the student center whichever note comes naturally.

EXAMPLE #1 (sound file)

#2 – NO TONE, RUSHING AIR In this instance, there are two possible causes:

a. Embouchure not formed tightly enough.

b. Airstream restricted by closed throat and/or raised tongue.

EXAMPLE #2 (sound file)

REMEDY: Re-form the embouchure (“OH-OO- SQUEEZE”) and tell the student to grip more tightly on the imaginary “tube in the center of the lips.” Also, stress the importance of saying “OH” to keep the throat open and the tongue down.

#3 – THIN, PINCHED TONE This sound:

EXAMPLE #3 (sound file)

is caused by a combination of the following:

a. Embouchure formed too tightly; lips pinched together.

b. Insufficient volume of air passing between the lips.

“Loosen the grip on the tube.”

REMEDY: Instruct the student to “loosen the grip on the tube in the center of the lips.” Also, reiterate the concept of taking a deep breath with the “yawn” type of feeling in the throat and then expelling the air as rapidly as possible. A relaxed diaphragm is especially important to allow maximum expulsion of air.

#4 – GARGLED TONE This “split” tone is a result of:

a. Lips not “gripping the tube” tightly enough to center the pitch.

b. Lips folding over the teeth causing a double vibration.

EXAMPLE #4 (sound file)

REMEDY: If gripping the tube more firmly does not solve this problem, have the student re-form the embouchure using the mouthpiece ring and check to see if the lips are staying even with the edges of the teeth, not curling over the top. (When the “OH-OO-SQUEEZE” embouchure is formed correctly, the lips will not curl over the teeth.)

#5 – STOPPED or INTENSE AIR ONLY This less frequently heard sound:

EXAMPLE #5 (sound file)

is a severe exaggeration of #3 (THIN, PINCHED TONE). The lips have been pinched completely together and only extreme force of air causes any sound whatsoever.

REMEDY: Instruct the student to “loosen the grip on the tube in the center of the lips.” Stress only “OH-OO” in this instance.

GENERAL EMBOUCHURE PROBLEMS

- Make sure the corners of the mouth are not drawn back into a smile type of set. The corners should be very firm but held in the natural, lateral position.

- The angle of the mouthpiece to the lips is very important. Problems here can be spotted quite easily and very simply corrected. The mouthpiece should be placed against the mouth while holding the jaw in a very natural position. The angle will vary greatly from student to student, depending on the degree of over- or under-bite of the teeth. Don’t let the student jut his jaw forward to meet the mouthpiece. Have him lean slightly forward or backward with the tuba to the point where the mouthpiece sits at a natural, comfortable angle.

- Don’t allow the student to puff out the cheeks. When the cheeks are puffed, the corners of the mouth can not set firmly and the basic embouchure set and control are lost. With emphasis on gripping the tube, the cheeks will not puff.

- Using the mouthpiece ring, check to make sure that the lips do not go into a radical pucker. Sometimes, if there is too much emphasis put on the “OO” sound in formation of the embouchure, there will be a tendency to push the lips too far forward into an exaggerated pucker. This will result in loss of control and “bracky” tone quality.

CHANGING PITCHES

If the embouchure appears to be formed correctly and the student is having good success in producing the first tone on the tuba, move immediately to a note other than the one which was most natural at first.

If the first note produced was F below the bass clef staff, ask the student to now try the second line B-flat. To accomplish this, tell him merely to tighten more on the tube and blow more air. Remember: Don’t tell the student to push the air, as this will bring the tight diaphragm into the picture, a condition we do not want!

“Nicklaus tries to recreate the feeling of a good shot.”

Once he has produced the second tone, ask him to playback and forth between F and B-flat, remembering what each feels like. This will begin transference of the feeling into the memory bank so that it may be recalled whenever a particular pitch is needed. Jack Nicklaus once said that when he steps up to the ball to hit a golf shot, he does not try to concentrate on all the minor details which go into hitting the shot correctly; he simply tries to recreate the overall physical sensation of what it feels like to hit a good shot.

Once he has produced the second tone, ask him to playback and forth between F and B-flat, remembering what each feels like. This will begin transference of the feeling into the memory bank so that it may be recalled whenever a particular pitch is needed. Jack Nicklaus once said that when he steps up to the ball to hit a golf shot, he does not try to concentrate on all the minor details which go into hitting the shot correctly; he simply tries to recreate the overall physical sensation of what it feels like to hit a good shot.

The correlation to tuba playing is obvious: Once we have gone through all of the processes which form the embouchure and produce the sound, we should then concentrate on the overall physical feeling which produced that sound. Then we should attempt to recreate that feeling each time we wish to play a certain note.

EXAMPLE #6 (sound file)

If the first pitch produced by the student was second-line B-flat, follow the reverse procedure: have him relax the “grip on the tube” and blow slightly less quantity of air in order to produce F below the staff.

ADDING THE VALVES

Now ask the student to take a large breath and play down by half-steps from B-flat to F (open, 2, 1, 1 & 2, 2 &3, open). It is important to start from the top note and work down as this is much easier than working up. The student’s chances of immediate success are much greater as well. Also, have the student play this chromatic exercise without use of the tongue; at this point, it will only get in the way and cause problems. Instruct the student to think of air movement being exactly the same as playing a single long tone so that he will blow through the chromatic run.

EXAMPLE #7 (sound file)

The next step is to play the chromatic run starting on F and ascending to B-flat. This will generally be more difficult but can be made easier by playing a crescendo throughout the exercise. This will tend to keep air moving throughout the run and will make the F to G-flat break much easier.

EXAMPLE #8 (sound file)

MOUTHPIECE BUZZING

It is my contention that the single most neglected exercise by most brass players is mouthpiece buzzing. Let’s face it; there is nothing inside a brass instrument that will itself produce sound. The sound is produced by buzzing the lips–sound which is amplified by the instrument. Therefore, it stands to reason that anything played on the instrument can also be played on the mouthpiece alone if the embouchure is properly performing its function.

So, HAVE YOUR STUDENTS PRACTICE BUZZING WITH THE MOUTHPIECE. They can play scales, etudes, songs, anything. One word of caution: Don’t let them just buzz indiscriminately. Make sure they produce definite pitches as this is the only way in which mouthpiece buzzing is beneficial. Also, do not have them buzz their lips without a mouthpiece or a mouthpiece ring to define the area of lip which must be trained and controlled. Buzzing the lips without the mouthpiece will provide nothing useful in embouchure training.

Anything done with the mouthpiece can and should be done with the mouthpiece ring as well. You will be amazed at the results.

EXAMPLE #9 (sound file)

FOUR VALVE TUBAS

I have often been asked about the purpose of the fourth valve on the tuba. It is really quite simple as it is merely a compensating valve used to help bring low B and low C in tune. In fact, it is an F attachment much like the one on bass trombone; however, due to problems with intonation, it can not be used in exactly the same manner. The fourth valve is used as a substitute for the 1 and 3 valve combination, which means that instead of playing low C with 1 and 3, we can play it was 4 alone. Instead of 1, 2, and 3 for low B natural, we can play it with 2 and 4.

Even with the fourth valve, these notes will tend to be quite sharp, so the fourth valve slide should be pulled out. The exact amount to pull the fourth valve slide will vary and should be determined with each instrument individually.

The fourth valve can also be used to produce the notes between low E and pedal B-flat, but due to intonation problems in this register, the fingerings usually need to be altered:

- E – 2 and 4

- E-flat – 1, 2, and 4 (On some instruments this E-flat can be played 1 and 4, but normally all pitches from E-flat on down must be fingered a half-step low to be in tune.)

- D – 2, 3, and 4

- D-flat – 1, 3, and 4

- C – 1, 2, 3, and 4

- Note that low B natural is lost as a result of pitch compensation. Don’t worry; it won’t likely be needed.

INTONATION

Every student can and must play in tune from the very beginning! As soon as a note is introduced, there must be instruction that produces correct tone quality. Since out-of-tune notes seldom contain proper tone quality, it follows that attention to one cures the other. Note the following examples of natural pitch tendencies on tuba which, when corrected, also improve tone quality:

LOW B: natural sharpness and thinness, then corrected. Using 1, 2, and 3 combination.

EXAMPLE #10A (sound file)

Correction by opening the throat to maximum “OH” shape.

LOW B: natural sharpness and thinness, then corrected by using 2 and 4 valve combination.

EXAMPLE #10B (sound file)

BOTTOM LINE G-FLAT: natural flatness and corrected. The natural flatness of the 2 and 3 valve combination must be corrected by “lipping” up. This fact often makes “centering” of G-flat a problem. Increasing the “grip on the tube” often a help pitch here.

EXAMPLE #11 (sound file)

THIRD LINE D: natural flatness and corrected. The problem of flatness on D is similar to the G-flat; however, several alternate fingerings are available for the purpose of comparison to locate the proper pitch level. Valve combination 1, 2, and 3 is an in-tune possibility that can be used to show the student how much to lip up the open D. Even 1 and 2 (sharp in pitch) can serve as an aid in this regard.

EXAMPLE #12 (sound file)