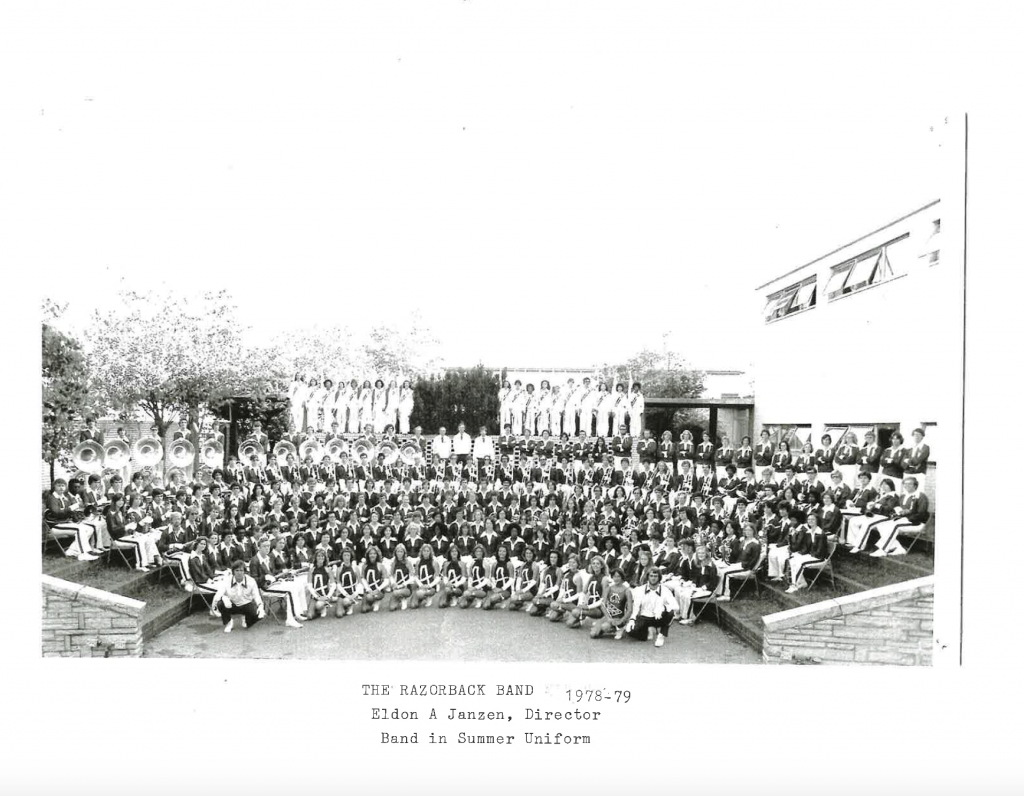

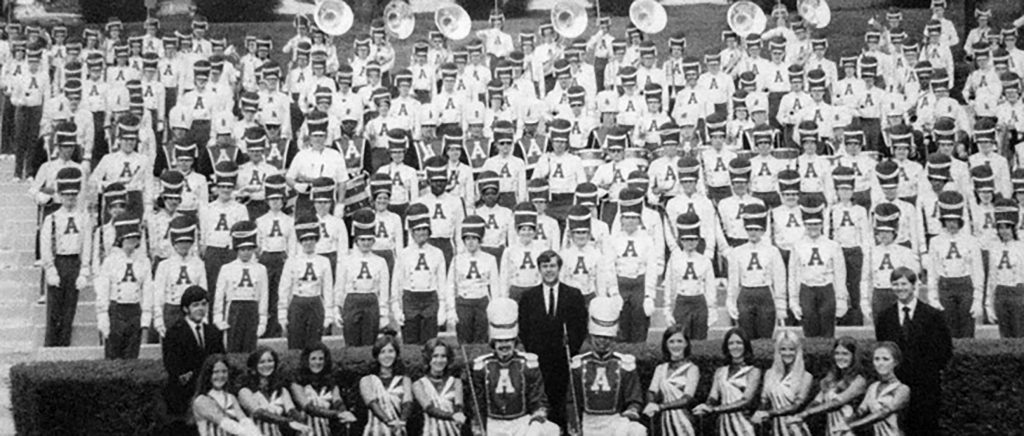

Eldon Janzen and The University of Arkansas Band Program

The weather during February can often be unpredictable for residents of north Texas. Some years, you can get a sunburn while other years you’re shoveling snow and trying to stay warm while waiting for the electricity to return after an ice storm. February 1970 was cold. On a day when most people in Irving, Texas, were trying to stay warm inside their homes, Eldon Janzen was at the top of a step ladder painting a front of his newly-purchased home on Beacon Hill Drive where he lived with his wife, Nel, their daughter, Jana, and their son, Scott. Armed with his paint can and brush, Janzen was trying to ignore the cold and finish his project when the front door opened. Nel was making her way across the front lawn with phone in hand to inform him that someone was calling from the Arkansas Gazette. As he descended the ladder and took the phone, Janzen was about to field his very first question from the media as the new Director of Bands for the University of Arkansas. “Mr. Janzen, I’m calling to ask what you’re planning to do about ‘Dixie.’” His first thought was that Dixie must be a band member. Unfortunately, as they would eventually discover, that was not the case. The next few years would have been much easier for the Janzen family if Dixie had been a person. The phone call and their first drive up US Highway 71 toward Fayetteville might have been omens of what was in store as the Janzen family began a new chapter in their life.

“I don’t quite understand the problem, but I will get back with you when I’m in Fayetteville,” was Eldon Janzen’s final words to the Arkansas Gazette reporter who had called him at his Irving home that cold day in February. With no details, Janzen assumed “Dixie” was an actual person in the band who was an embarrassment for some reason. It is entirely possible that he eventually forgot about the conversation with the Arkansas Gazette reporter altogether. If Janzen had indeed forgotten, he was enthusiastically reminded immediately after his arrival in Fayetteville. In fact, it seemed that “Dixie” had become an important issue to the entire state of Arkansas.

The pregame ceremonies at all Razorback home football games traditionally ended with the playing of “Dixie.” The song would inspire an enthusiastic response from the home crowd. The audience’s response for “Dixie,” perhaps even greater than for Arkansas Fight, the University of Arkansas’ official fight song. While Janzen’s main focus was on preparing the Razorback Band for their first performance, he knew that he would eventually be forced to confront the “Dixie” issue. He also knew that a decision would be expected that, once made, would be impossible to reverse. Whatever his decision was, he knew that he must not show hesitation nor any type of ambiguity. When Janzen was asked about his decision, there was no delay in his reply:

I didn’t even have to think about it. I felt that it would present a danger to the students in the band and I saw no reason to subject them to any possibility of bodily harm. I didn’t really have to think about it very seriously. The night before I arrived, they had a pep rally and a young black man was shot in the leg. I wrote the president of the university and there was no help forthcoming from anyone and the decision was solely my own. I had several black students in the band and they were great students. I knew that, if the band were to resume the playing of Dixie, it would result in political upheaval. It would obviously be the wrong thing to do.

As soon as Janzen arrived on campus his telephone began to ring and letters started pouring in. The steady influx of questions prompted Janzen to write the president of the university, David Mullins. Janzen was very clear with his communication. This was his first contact with the university president and he was aware of the importance of first impressions. He expressed two points of concern–his belief that the Arkansas Band should not be used as a political instrument and his concern for the safety of his students. President Mullins responded by thanking Mr. Janzen and went so far as to indicate that he agreed with Janzen’s decision, but that was all. The letter was encouraging in nature, but Mullins made it obvious that he would provide no help or statement of support. Janzen’s decision would be solely his own.

As expected, the debate over “Dixie” eventually led to a conversation between Janzen and Arkansas’ legendary football coach, Frank Broyles. Known as a traditional southern gentleman, Broyles was not hesitant to request that Janzen reconsider his decision and resume the tradition of playing “Dixie.” Broyles’ interest in continuing the tradition stemmed purely from the knowledge that the tune created an overwhelming or “rowdy” reaction from the home crowd. In Janzen’s own words:

Frank Broyles was a god-like figure on campus and he wanted the band to continue playing Dixie. He was interested in crowd support and it really roused the crowd up. I had to tell him right off that I didn’t have any plans to use that song again.

Janzen knew that he would need help from another source to maintain his position, and it would need to be someone who not only supported his decision but who was also someone in a position to encourage this deep-south audience to go along with it. He began by listening to recording after recording of newly-published music for marching bands that were distributed each year by the music publishing companies. Eventually, he ran across a piece called, Swing March—and it fit. Janzen describes the fortunate stroke of luck that happened next:

My neighbor at that time was Wally Engels, the announcer for all home Razorback football games. I asked him if he would encourage the audience to chant, “Go Hogs Go,” during the drum cadence at the end of Swing March. Wally agreed, and it worked well. Wally continued to encourage people to get involved, it finally caught on and it remains a tradition today. Unfortunately, the uproar over not playing Dixie never really died down with the older folks.

There were many letters of protest—some eloquently written, others were less than civil, still others insulting and threatening. Janzen still has the file-folder filled with protest letters, each expressing the same sentiment, insisting that the band resume playing “Dixie” at football games. University students were given the opportunity vote to determine “Dixie’s” fate. The first vote supported the playing of “Dixie.” However, a second vote was arranged weeks later that reversed, albeit by a very narrow margin, the feelings of the student body. The second vote indicated the student’s desire to discontinue the practice.

The controversy surrounding the Arkansas band’s playing of “Dixie” had been increasing since the year prior to Janzen’s arrival and was now reaching a boiling point. On the evening prior to the 1969 national championship game between Arkansas and the University of Texas, the band marched to the Greek Theater for the traditional pre-game pep rally. Upon their arrival, the campus group, Black Americans for Democracy, was occupying the seating area reserved for the band to stage a peaceful protest against the playing of “Dixie.” A protest was also planned during Arkansas’ game against Texas the following day if the band played Dixie, something university officials desperately wanted to avoid since President Nixon would be in attendance. Avoiding the possibility of conflict, the drum majors marched the band to the Wilson Sharp House which housed the Arkansas football team. Once there, an impromptu pep rally was staged for the members of the football team who were present. After the performance at Wilson Sharp House, band members were making their way back up the hill to the band hall when one band member noticed that the African-American members of the band were no longer with the band. Upon returning to the band hall, they found that their African-American colleagues, rather than marching to Wilson Sharp House, had returned to the band hall to wait for their fellow band students to return.

Nathanial Thomas, Tyler Thompson, and Richard Wheeler were among the band students who participated in the conversation that followed between black and white band members. When interviewed, Wheeler described this meeting as being a “heart-to-heart and honest conversation between white and black band members.” Wheeler adds,

We (the white student band members) didn’t fully understand how the playing of “Dixie” actually impacted the black students of the band. We sat in the band hall that night for a couple of hours talking about it. In the end, the white band students realized the depth of resentment the black band students had for “Dixie.” They (the African-American students) were our friends and it was during this meeting that Sanford, among others, made us realize how painful the images represented by the song were to them. I remember the statement being made, ‘You’re our friends-if Dixie hurts you, it hurts us and we are going to be with you on this. We have other fight songs we can play. We don’t need to play “Dixie.”

Almost 50 years after the event, Wheeler could not fully recall the full circumstances, but he remembers that Arkansas football coach, Frank Broyles, later requested a meeting with students, including members of the Razorback Band. During this meeting, Wheeler recalls Broyles informing the student delegation that he had been approached by African-American student-athletes who voiced their feelings and resentment concerning “Dixie.” He indicated that some of the African-American football players also expressed the same feelings. After hearing from all the students, Broyles agreed that “Dixie” should not be played.

The day after the pep-rally incident, the 1969 game between Arkansas and Texas went off without a hitch. Reverend Billy Graham provided the pre-game invocation. Other than the fact that Arkansas lost to Texas 15-14, the event exceeded every expectation held by ABC TV and the football world. It would always be known as “The Game of the Century.” It was also the last regular season game of the centennial year of NCAA football and the final college football game to be broadcast on national television between two Division I football “powerhouse” teams—neither of which had even one African-American player on their roster.

As Janzen started his second year as director for the University of Arkansas Bands, as far as he was concerned, the “Dixie” issue had been resolved. It would never be performed again by the Razorback Band. “But the good ole’ boys in Arkansas just wouldn’t let it go,” stated Janzen. Even with the student vote confirming Janzen’s decision, the calls and letters kept coming. Many of the letters were addressed to the university president, David Mullins. One person that called Janzen every year was the president of a large bank in Little Rock. Janzen explained,

I finally got to the point where I could talk to him without allowing him to upset me. He would call and say, “Well Professor, is “Dixie” in your line up for this year?” And I’d say, “Mr. Bowen, we will not be playing that song this season.” Eventually, we were able to converse in a fairly friendly manner and after about ten years, he finally quit calling.

Unfortunately, it seemed as though Janzen’s efforts and those of anyone who had the courage to support him had little effect. “The audience kept wanting and demanding to hear “Dixie” played at football games,” It wasn’t the song itself so much as the idea behind the song and what it represented to other people,” Janzen commented.

Janzen became proficient at running off people who visited the band at games to cause trouble. There was an incident at one game in which he was approached by an obviously inebriated student. The student staggered toward Janzen carrying what was obviously a water pistol. Pointing the water gun in Janzen’s face, the student muttered the words, “I want you to play Dixie!” To which Janzen replied, “I’m sorry, we just don’t have that song in our folders.” Obviously dissatisfied with Janzen’s comment, the student emptied his water gun directly into Janzen’s face from point-blank range. In his drunken stupor, the young man failed to notice that Janzen was at least a foot taller than he. Perhaps he man didn’t consider until it was too late that emptying a water gun in Janzen’s face, even one loaded with straight bourbon, could result in his being lifted completely off the ground and launched into the student section. There was also the occasional drunk who would stagger into the middle of the band at a football game. As Robert Bright reminded Janzen: “You did throw a drunk over the railing in Little Rock!” This fact is true, but Janzen didn’t raise his voice in the process.

Unfortunately, there were off-campus incidents as well, mostly performed by pranksters, people that were angry, members of the pep club organization, or individual students. Scott Janzen, who was five years old about this time, once lifted his bedroom window and yelled at them from his room. Janzen smiled and added, “Scott probably yelled some specific words that he possibly could have overheard somewhere around the house.” What was likely the most disturbing incident happened when the Janzen family was living in a more remote location of Fayetteville. The Janzen family was abruptly awakened in the middle of the night by a loud commotion coming from the front yard of their home. Upon opening the front door, Janzen and his family discovered that their midnight visitors had left something that was easily understood: a wooden cross had been placed in the front yard, doused with fuel, and set on fire. Janzen downplayed that aspect of the incident as the probable result of sophomoric behavior by a few, possibly drunk, individuals. However, Janzen’s concern heightened upon the receipt of a letter, in which the writer, angered at the loss of “Dixie,” included his intent to, “kill that loud-mouthed little bastard son of yours.”

Janzen knew that, Darrell Brown, an African-American student, had been shot in the leg the year before, so a letter that threatened to kill his five-year-old son had to be taken seriously. He presented the letter to the chief of police for the city of Fayetteville and asked two questions. He first asked the police chief if he thought that the letter should be taken seriously. The chief’s answer was, “Absolutely!” Janzen was not prepared for the chief’s next bit of advice. When prompted for a suggestion or the appropriate course of action to take, the police chief patted the right front pocket of his trousers and said:

When I go out campaigning or anywhere that takes me into a large group of people, I always carry my .38 caliber pistol right here in my pocket where I can get to it. And my advice to you is to do the same.

Forty-eight years later, Janzen can still recall the conversation.

That’s all the advice he gave me. I thought, “Boy there’s no help here! Carry a gun? And this is the police chief?”

Janzen returned to campus determined to follow through with his decision regarding “Dixie” and protecting his students—without a gun.

Surrendering “Dixie”

While there were constant reminders of the emotion stirred by the absence of the song “Dixie,” there were also several events that provided Eldon Janzen with hope that the intense resentment might be fading. The first event centered around the selection of the Razorback Band’s two drum majors for Janzen’s second marching season at Arkansas. One of the candidates was Sanford Tollette, a saxophone player from Little Rock. If selected as a drum major, Sanford would not only be the first African-American drum major for the Razorback Band, but also the first African-American drum major in the Southwest Athletic Conference and possibly the first black drum major to lead the band at any predominantly white university in the country. Sanford was smart and very well-liked by the members of the Arkansas Band. When auditions were held, Sanford’s audition was so well performed; his control and mastery of the components required of each applicant were so perfectly executed it was evident that he was overwhelmingly the best choice. Regarding Sanford Tollette’s selection as drum major, Janzen adds, “I didn’t receive one single phone call, note, or letter regarding the selection of Sanford as drum major because, once people had the opportunity to watch him, he did such a good job that there was no way anyone could criticize him.” Sanford Tollette was not simply a good drum major, he was excellent. Janzen’s courage combined with Sanford’s loyalty and dedication to Janzen had a positive effect on the culture of the Razorback Band that would continue to influence the program for years to come.

Unfortunately, not everyone was supportive. Prior to each rehearsal, Janzen would meet with Sanford to discuss the goals and plans for that day’s rehearsal. It was on such a day that Sanford sat in Janzen’s office ready to begin their pre-rehearsal meeting when Eldon received a phone call from Coach Broyles.

Remembering this call, Janzen stated:

Sanford Tollette was in my office and could hear the conversation when Coach Broyles called. I’m sure that Sanford remembers this conversation very well because when I was talking with Frank on the phone, Sanford was in there for his regular briefing before the rehearsal. And Sanford remembers me saying, Coach that’s something I can’t do and we terminated the conversation. That was when I approached David Mullins, the president of the university, and asked if he would publicly support me, but he refused. It was just something he wasn’t willing to do.” Stanford remembers Janzen ending the conversation and saying, ‘Son, you are learning that there are things in life that are worth fighting for, and some could be worth dying for.’

Sanford’s account of the phone conversation between Janzen and Broyles follows Janzen’s version almost word for word, with one exception. Tollette’s recollection included a comment by Coach Broyles’ regarding funding. The comment was not a direct threat but rather a hypothetical question intended to remind Janzen of what might happen if he did not cooperate. At the time, the Razorback Band was in desperate need of new uniforms, something that Janzen was concerned about. Tollette recalled that there may not have been a direct threat to withhold funding from the athletic department if Janzen didn’t agree to play ‘Dixie.’ He did remember Coach Broyles mentioning that, if the football team should not have a winning season, it was possible that he would not to have enough funding for some of the groups that play important roles at the games. In Sanford’s mind, he was referring to the band.

Tollette’s account of this conversation was a surprise for Richard Wheeler who was the band’s uniform officer at the time. “I never heard of any connection between not having uniforms and Coach Broyles; however, I was given the assignment of tracking down enough red blazer-type coats to outfit the entire band for the upcoming season because we did not have the funds to purchase new uniforms. I just never made the connection.”

As I continued my discussions with both Wheeler and Tollette, I remembered that it wasn’t until the fall of 1975, my freshman year at Arkansas, when the Razorback Band finally received new marching uniforms.

Sanford also endured his own share of resentment, ridicule, and torment. When interviewed, Sanford recalls:

I was often called an ‘Uncle Tom’ by other black students for just being in the band. At one home game, I was standing with the band waiting for the first half to end when some student wandered up to me and said, ‘Play “Dixie,” nigger!’ When on guard and prepared, I was always able to maintain my composure. I didn’t want to give them the satisfaction of knowing that they got to me. But this took me by surprise and I began to cry. Mr. Janzen saw me and immediately ran over and confronted the student using language that really surprised me. I’d never heard him use profanity, but it dawned on me that he was as upset about it as I was. Mr. Janzen cared for me and encouraged me. I’d do anything for him and there was absolutely no way that I was going to let him down. Mr. Janzen made no apologies for the student’s behavior. Instead, he said simply, ‘Think you can get the band up for the fight song?’ I said, ‘Yes sir!’

Sanford never let Janzen know that he had also received his share of hate letters, unsigned notes left on his door, and even death threats. Now 67, he admits that returning to Fayetteville often brings on bouts of depression, severe anxiety, and other symptoms of PTSD. Almost 50 years later, I could still detect the emotion in Tollette’s voice when he expressed his respect and admiration for Eldon Janzen. As I listened over the telephone to Tollette talk about his experiences and, having myself been in Janzen’s office many times, an image began to appear in my mind. I closed my eyes and I could see Janzen, a white man who was born and raised in the south, sitting behind his desk, discussing rehearsal goals with this young man of color who was one of fewer than 100 African-American students attending the University of Arkansas at that time. Janzen addressed his new drum major with respect. He became Tollette’s mentor and an encourager in dealing with the people who resented him as a leader. “I always knew that Mr. Janzen had my back and that I could depend on him.” Relationships such as that between Eldon Janzen and Sanford Tollette were extremely rare.

The second event helped put an end to the problems associated with “Dixie” was a published statement drafted by the University of Arkansas Music Department faculty supporting Janzen’s stance. It was the first letter from any person or group of people that was published to support Eldon Janzen and his stance on “Dixie.”

Perhaps the final event that led to Dixie’s demise was an editorial that appeared in the Arkansas Gazette supporting Eldon Janzen’s decision to discontinue the use of “Dixie.” Although a few letters would continue to arrive each year, few if any were threatening in nature and it seemed that the war for “Dixie” was subsiding. Eldon Janzen’s last comment about the conflict was a short and simple, “It was a completely political issue that surrounded the band but I believe that the experience actually strengthened the resolve of the band students.”

Janzen also recalled an incident that occurred at a meeting of the Fayetteville Lions Club:

In those days, the university didn’t have any black professors or administrators. So, they finally hired a ‘token’ black. His name was Harry Budd. Harry was a person of true quality and he had a beautiful singing voice. When I joined the Fayetteville Lions Club, they immediately appointed me as song leader. It was customary to begin our meetings by singing a song together. Each week when I stood to lead the song at our meetings, someone would say, ’Let’s sing Dixie.’ The day that we inducted Harry into the Lions Club, I was getting ready to lead the song and I wasn’t about to let those SOB’s encourage me to sing Dixie. So, I just picked a number out of the air and said, ‘Let’s sing number 89.’ Unfortunately, song number 89 turned out to be ‘Old Black Joe.’ Harry and I shared a pretty good laugh about that. I mean, he thought that was pretty funny.

Postscript

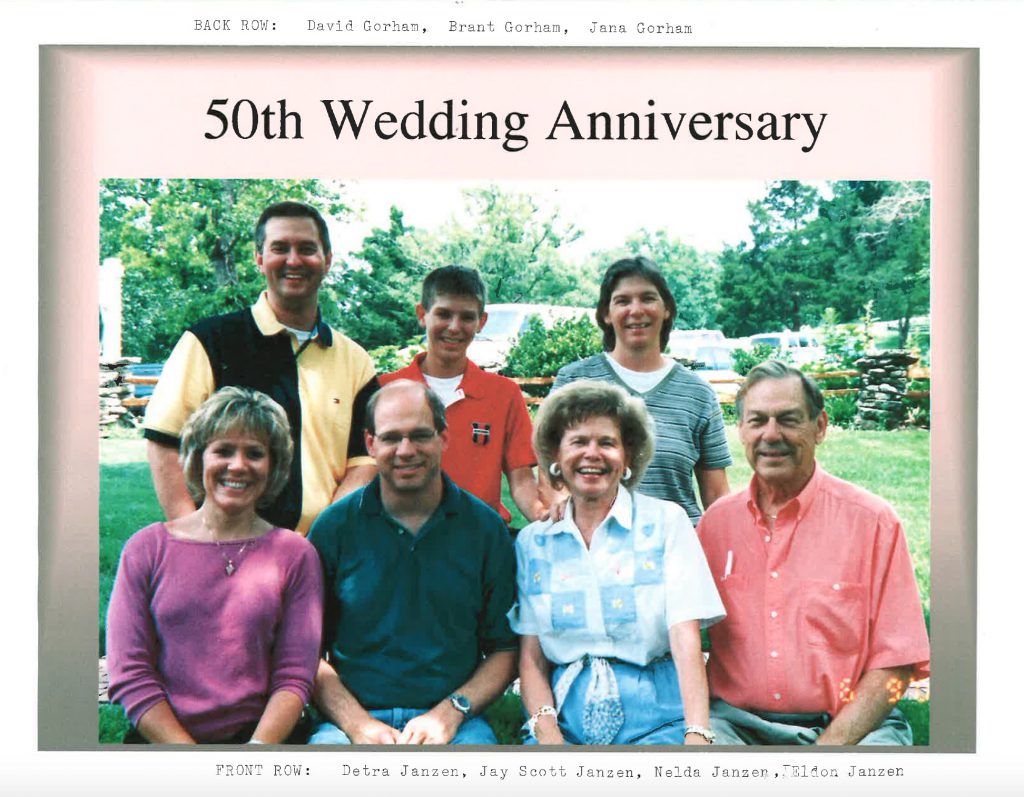

The years I attended the University of Arkansas and was a member of the Razorback Band were some of the best years of my life. While working on this article, I was astounded at how few of my friends and colleagues, those of my own generation and those who went before me had even heard about the events surrounding “Dixie.” It was almost as if it had never happened. But it did. As Robert Bright would tell me in our final interview in July of 2018, “We just tried to keep that stuff away from the students.” Then it occurred to me. What would Mr. Janzen want his legacy to be? It’s only my personal opinion, but from listening to him speak, I don’t think he has any desire for “Dixie” or any of the events that took place during that time to have any place in his legacy. Eldon Janzen’s legacy is evident in the lives of his children Jana and Scott. His legacy also lives in the influence that he has had upon his colleagues, his profession, and every student who was fortunate to have him in their life.