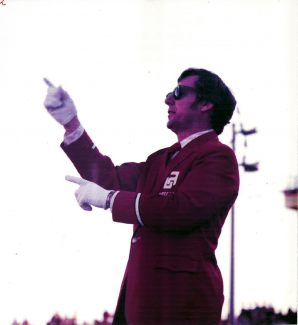

Eldon Janzen was in his third year as Supervisor of Music for the Irving Independent School District in Irving, Texas in spring 1970. Prior to moving into his administrative role, he had served as the band director at Irving High School for eight years and had gained the reputation as a successful young band director dedicated to old-style discipline and fundamental instruction. Janzen’s Irving High School Band was viewed by his colleagues as a top-tier performing group and one of the best band programs in Texas. He had also assumed an additional leadership role as president of the Texas Bandmasters Association. Janzen’s fast-track rise to this position was the result of the unexpected retirement of other TBA board members who were in line for the presidency ahead of him. However, within days of becoming the leader of the largest bandmaster organization in the country, Janzen made the decision to pick up his family and move to northwest Arkansas. His last official responsibility as the president of the Texas Bandmasters Association would be to preside over the annual convention traditionally held in San Antonio.

Janzen’s journey from Texas to Arkansas had begun during his years on the podium when he was hired to serve on a panel of judges for a band contest in southern Arkansas. The other two judges on the panel were Dr. Francis McBeth from Ouachita Baptist University and Robert Bright from Arkansas Tech. The contest provided ample time for the three men to become good friends and discover what they had in common–primarily their dedication to high musical standards, a strong work ethic, and the belief that establishing personal discipline was a prerequisite before any musical organization could attain a significant level of achievement. McBeth, a prolific composer of music for wind band, was already a well-known figure in music and music education. Janzen discovered that McBeth already knew of his success in Irving because McBeth was a graduate of Irving High School. Their mutual respect resulted in a strong and long-lasting friendship.

Robert Bright played an even more integral part in Janzen’s journey to Arkansas. Bright was known as the architect of the Arkansas Tech brass department which, under his guidance, was considered one of the best in the country. He and his friend, Irby Martin, who was in his first year as band director at Fayetteville High School after serving 12 successful years as the band director at McGehee High School, would meet often for coffee and discussions. Bright and Martin came to Fayetteville the same year and their opinions regarding the concepts of instrumental and ensemble sound and instruction were similar. In addition to both being new to Fayetteville, Bright and Martin had something else in common–Arkansas Tech. Irby received his music degree from Tech which was, beyond question, the school in Arkansas for future band directors, especially brass players.

When it was announced that the Director of Bands position was officially open, both Bright and Martin knew who the struggling Arkansas program needed. Rebuilding the Arkansas band program was not expected to be easy. The new director had to be someone who could establish discipline within the organization and increase the size and quality of the band by reaching out beyond state borders to recruit talented students. The new director needed to be a solid fundamentals teacher who could also develop the advanced skills of musicianship in students who were already at the university level. It was a monumental task that must be accomplished while winning the hearts and minds of the students, the university, and residents of the state of Arkansas.

As Bright would say when interviewed, “We knew that Janzen was the guy who, as the old saying goes, could turn a sow’s ear into a silk purse.” When asked if he had any prior knowledge of the University of Arkansas or the reputation of the Razorback Band, Janzen recounted his first impression:

My band from New Boston High School was invited to the Cotton Bowl game to perform in their annual pre-game extravaganza back when Harry Barton was organizing it. Harry would traditionally invite five bands that he felt were the best in Texas to perform the pregame ceremonies. The tradition was that after your band had participated in the Cotton Bowl pre-game, and all went well, you would continue to be invited back. There was one year when I conducted the pre-game show at the Cotton Bowl. Arkansas was playing Nebraska on New Year’s Day. During the pre-game, the Arkansas band came on and, with them, were some students pulling this giant bass drum. It was like a bunch of clowns out there. That was my first impression of the Arkansas band and I still remember watching those guys pulling that bass drum around and seeing it fall.

Closing the Deal

Knowing that there needed to be other recommendations to support his candidate, Bright made the necessary calls to those he knew could attest to Eldon Janzen’s qualifications and his ability to accomplish what would be a complete overhaul of the University of Arkansas band program. The contacts that Bright called were young men who were establishing their reputations by building great high school and university band programs. Today, they are viewed as icons in the wind-band world, prolific composers, and master educators.

Bright’s first contacted his long-time friend, Dr. Francis McBeth and then Dean Killion, the Director of Bands at Texas Tech University. Bright also contacted James Sudduth, a young high school director from west Texas. Each person had positive comments about Janzen and encouraged Bright to continue his pursuit of Janzen as Arkansas’ next director. Dean Killion added that he had even gone as far as securing copies of videos and comment sheets of Janzen’s marching drills for use in teaching future band directors.

With the groundwork complete, Bright now had the proof he needed to demonstrate to university officials Eldon Janzen’s qualifications as a fundamental teacher and one who was capable of establishing the disciplinary skills necessary to turn around the struggling Arkansas band program. Bright was certain that Janzen was not only the right person for the job but perhaps the only person capable of producing that “silk purse.”

Eldon Janzen’s decision to accept the offer and become the next Director of Bands for the University of Arkansas seemed to be the logical next step in his career as a music educator. He was in his third year as the chief administrator for the band program in Irving, Texas, a district which now served over 25,000 students and, tiring of administration, he was ready for a change. The opportunity to move back into the classroom and to work with college students seemed to be a logical next step. When asked what finally convinced him to accept the position at Arkansas, Janzen explained:

I had been in administration for three years and had identified the problem areas that needed to be addressed within the band program. I felt that I had solved all of the problems that I was able to solve. I had stated my case and had arrived at a point where I felt that I had accomplished all I was capable of accomplishing. I was also growing tired of being in administration and I missed making music and working with students and seeing the improvement that takes place during the rehearsal process. The opportunity that Arkansas provided appealed to me and seemed like a logical move to make.

Janzen knew that the University of Arkansas job would not be an easy one. The Razorback band was not known for their performance quality. Indeed, the 1970 Sugar Bowl performance, which was witnessed by millions on national television, was not only an embarrassment to the University of Arkansas but also to many residents of the state. This humiliating performance, viewed by millions of Americans on television, was attributed to the band students’ poor behavior the prior evening. With little or no established disciplinary standard, many Razorback band members were permitted to roam freely through the streets and bars of New Orleans.

A former member of the Arkansas band who participated in that performance stated:

I can still remember marching the show at halftime and making a wrong turn that was impossible for anyone to miss. When I made that wrong turn, it caused a chain reaction with those around me. So many were either hung-over or still drunk from the previous evening’s activities. It had to be the worst performance of a university band that you could possibly imagine—and it was on national television.

The two largest newspapers in the state, the Northwest Arkansas Times and the Arkansas Gazette, published articles that referred to the Arkansas band as, “The Stumbling 100.” There would be many more nationally televised games to come and the moniker demonstrated to the university that changes were necessary.

Robert Bright had been hired during the summer prior to the 1969-1970 school year. A graduate of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, Bright had built the brass department at Arkansas Tech and also served as assistant band director to Gene Witherspoon. John Cowell, the chairman of the music department at the time, had hired Bright the previous year. Cowell was very receptive to improving the band program. “I was hired to clean up that mess,” Bright recalls Cowell’s telling him. Cowell knew that the culture of the Arkansas band program had to be changed. Bright was adamant with Cowell about the need to recruit quality students. He stated, “We must recruit. If schools like Eastman, Michigan, Juilliard, Indiana, North Texas State, and other schools in that caliber had to recruit, then Arkansas had to recruit. I told him that if I couldn’t get that done in three years, he wouldn’t have to go to the trouble of firing me because I’d quit.” Robert Bright recalls the condition of the band during his first year on campus during the 1969-70 school year:

The national championship game with Texas was on national television and we knew that President Nixon was going to be attending. The director was arranging how the band was to sit in the stands. There were twelve sousaphones in the marching band, so he said, ‘Okay, those of you who have a mouthpiece and a set of bits and actually play, I’d like to have you seated over here and those of you who don’t play sit over there.’ Well, ten out of the twelve sousaphone players went over and sat with others were not actually playing. There were only two students that played. The other ten didn’t even have mouthpieces or bits.

This dire situation was the one into which Janzen entered when he accepted the University of Arkansas position.

In 1970, Fayetteville, Arkansas resembled a village more than a city. With a population of approximately 30,700 people, it was much smaller than Irving, Texas. The Janzen’s initial trip to Fayetteville took them up US Highway 71 which was the main highway leading to Fayetteville. As Janzen moved his family from Texas to Arkansas, he still knew very little about the Arkansas band program or its condition. There were also questions regarding his new salary that barely matched what he was making in Irving. Thankfully, the dean of the school of music agreed to employ Eldon for the summer to give him an extra sum to compensate for the financial loss he experienced during the move. The financial help allowed the Janzens to make ends meet through the summer.

The Janzen Era Begins

Reality began to settle in for Janzen after he moved into his new office in the University of Arkansas band room. He began to realize that conditions were worse than he had anticipated and that Robert Bright, the person who had devoted so much time and effort in bringing Janzen to Fayetteville, would be his most valuable asset. Indeed, Bright would play a major role in Janzen’s success as the new director.

Janzen learned that a few Arkansas high school directors resented him because they believed they were qualified for the position. Janzen discovered that he was the only candidate considered for the job which was interpreted as a “slap in the face” to some who viewed the University of Arkansas as THE university in the state. There were also directors who were upset that an outsider from Texas was brought in and awarded the title of Director of Bands at their state university without one of “Arkansas’s own” even being considered for the job. Janzen shared that it took several years to overcome the hard feelings to the point that he and a few of his colleagues could engage in a civil conversation.

Building the Band Program

To improve the band, Janzen realized that he must make major changes. One change that Janzen implemented was stricter rehearsal expectations, an abrupt shock for the returning members of the Razorback Band. Compared to rehearsals under the former director, the atmosphere was now like that of a military organization.

But perhaps the most significant change of all was in the marching style. In previous years, the Arkansas Band espoused the marching style like the Big Ten Conference schools, incorporating high knee-lifts and eight-to-five marching steps. Janzen implemented a six-to-five marching style more characteristic of military bands. The new style was crisp and regal—a style that was uncomfortable for most of the returning band members. But because of Janzen’s discipline, the structure, and intensity of his rehearsals, and his detailed planning, the band looked good. Really good! And people noticed. Describing the students’ initial reaction, Janzen recalls:

First of all, the most drastic change was with the marching style. In addition, I insisted that they memorize the music and play it off. But once the students realized that they were getting better, it worked and it was all downhill from there.

Janzen had a unique way of accomplishing things, or rather getting others to accomplish things, while using very few words and without raising his voice. Perhaps it had more to do with the sound of his voice. Irby Martin, the band director at Fayetteville High School at the time, recalled a rehearsal one day prior to Arkansas’ opening game with Stanford. Martin recalled the students’ energy level during the rehearsal as somewhat sluggish. As the end of the rehearsal grew closer, Janzen calmly took two steps down his ladder, folded his arms across the top of the ladder and almost sympathetically said, “That’s okay boys and girls. You’re not on national television until tomorrow afternoon.” The pace of the rehearsal picked up. Instantly.

Janzen also had help from Robert Bright. Having a one-year head start on Janzen, Bright was the guy that any disgruntled student came to when upset with Janzen’s new way of doing things or, as Janzen would say, “when they had a beef with me.” He knew that Bright would take the time to listen to the student and then explain his reasoning, the “hows and whys” of his approach. Bright would point out the importance of patience and the need to look around and see how the band was rapidly improving as a result of Janzen’s methods. During our three interviews that took place over a period of six months, Janzen would repeatedly credit Robert Bright as the main reason for his success:

Robert Bright taught me how to be a college band director. He got me up here and he was my right-hand assistant. Bob and I shared the exact same philosophy and we were completely in sync—all the time. We never had a disagreement about what to do with something. He taught me the basics of how to be a college band director and when students became disenchanted with 6 to 5 marching or having to play off their music each week, they went to Bob Bright, and Bob laid it out in simple terms why it was the best thing for the band. I never sensed that the band students were not pulling for me and I never felt any pushback from the band or from any of the people who worked closely with me. If I was doing something that he sensed could be detrimental to personnel, he would come to me and give me advice and tell me what he felt was the most productive way to resolve the issue.

By August 1, Janzen’s first performance with the Razorback band was fast approaching. It would be a nationally-televised game between Arkansas and Stanford at War Memorial Stadium in Little Rock. The game, which was promoted by ABC as the “Kickoff” game of the 1970 NCAA football season, was to be played ten days prior to the first day of classes on the Arkansas campus. Preparations were made for the first rehearsal and letters were sent to the 180 students that were on the list that former assistant director, David Pittmon, had provided Janzen when he arrived. At that initial rehearsal, instead of the 180 band students, Janzen was expecting, only about 80 students showed up—and some of them were twirlers. As Janzen explained, “It was a phantom band. We realized that there were never 180 students planning to attend. The list was simply made up. If students happened to ask a question, they were asked to write their name on the list. At some point, the list turned into a list of students who had committed to being part of the Razorback Band.”

After the rehearsal, Janzen was, in his words, “down in the dumps,” and commented:

That first marching band rehearsal was a real ‘eye opener’ for me. Then Bright said, ‘Let’s go across the street [to Janzen’s office].’ Entering Janzen’s modest office, Bright grabbed the ‘phantom’ list of students and started making phone calls. Several students indicated that they had been promised full scholarships which, at that time, was about $200.00 per semester. Bob’s hard work paid off by bringing us quite a few new students that we desperately needed.

Bright’s efforts generated an additional 20 to 30 more students. By the time the Razorback took the field for their first performance, there would be 126 marchers—96 of whom were freshmen.

The First Public Performance for Janzen’s Arkansas Band

Game days for the Arkansas band included an afternoon pep rally at a hotel in a downtown hotel in Little Rock. The students would arrive in their pep-rally uniforms and change into their performance uniform between the pep rally and the football game. Janzen laughed as he recalled one event from that hot afternoon:

After the pep rally, it was hotter than blazes and we took the band to War Memorial Stadium and began searching for a place to change clothes. Well, we happened to meet some guy who let us use his back porch. We had never seen him before and we never saw him again but he let us change pants on his back porch.

The halftime performance that evening was the first time that the Razorback band marched six to five. The show included Karl King’s famous march, “Barnum and Bailey’s Favorite.” Janzen later learned that Karl King was watching Arkansas’ game with Stanford on TV. During the days immediately following the game, Eldon opened his mail to find a conductor’s score to “Barnum and Bailey’s Favorite,” autographed by King himself. The score is still on display in Janzen’s Fayetteville home.

In contrast to the high standard of personal discipline that Janzen established in his students, it was apparent that individual discipline was not a characteristic of the Stanford University Band. Stanford’s halftime performances, as with other aspects of their organization, were unorthodox, to say the least. The Stanford band students did not travel to Little Rock by bus or plane. Instead, those who had cars, drove while other band students hitch-hiked to Arkansas. The Stanford band director also attended the game but, like his band members, he provided his own transportation. He also chose not to sit with the Stanford band. Robert Bright added his memory of the Stanford band’s performance:

The Stanford band was known for performing satirically-themed halftime shows featuring controversial and outrageous subject matter. When they performed at the game in Little Rock, they concluded their show by marching to the sidelines, facing the audience, and dropping their trousers.

When discussing his first few years at the University of Arkansas, it was easy to pick up on Eldon Janzen’s personal characteristics. First, he would never credit himself with the responsibility for the Razorback Band’s transition from “The Stumbling 100” to “The Best in Sight and Sound.” He seemed quite content to pass these accolades on to others, particularly Robert Bright and Chalon Ragsdale, who joined the Arkansas band staff in fall 1975. Janzen is hesitant to complain about the challenges he faced during these early days. However, Janzen eventually shared his feelings:

People generally don’t know how bad it was. Most of the area band directors would avoid sending their students to the university unless the student wanted to come here for engineering or something like that. Bob Bright was really the key. He was able to get me in the door and he paved the way in building relationships with directors around the state and convinced them of the positive direction the University of Arkansas band program was moving.

Janzen stated that he always seemed to have a nucleus of good players and still remembers them by name–Bruce Martin, Susie Skinner, and Fred Lipscomb–just to mention a few. Quality students tend to attract other quality players. But it was a gradual process and he and Robert Bright had to spend a great deal of time traveling around the state and throughout Texas and Oklahoma recruiting talent.

Janzen and Bright spent countless hours on the road visiting schools and band directors. When there wasn’t a pre-game pep rally on campus that required them to remain in Fayetteville, they went on the road every Friday night attending high school football games and visiting with band directors. “Bob would sometimes select a school that we would visit, and sometimes we would just go to any school who would have us,” recalls Janzen. Janzen’s first marching clinic in Arkansas was at Gravette High School in Gravette, Arkansas. Jerry Ratzzlaff, the director at Gravette, was so popular in his community, he could have been elected mayor. Jerry extended the invitation for Bright and Janzen to visit and promised them a good steak dinner after the clinic. The band from Siloam Springs also attended and Bright and Janzen certainly didn’t mention any expectation of payment. This visit was Janzen’s first to Gravette and he admits that he was not familiar with the smaller towns and communities that were in the “boondocks.” Bright knew the way and when they finally arrived in Gravette, they looked for the lights of the stadium, drove in, parked the car, and got out. Janzen recalls the greeting:

Almost immediately, two guys with money aprons came to us and said, ‘That’ll be $5.00 each.’ I asked what was going on and said, ‘We have two university professors coming into the clinic and we’re charging everyone five dollars admission.’ I said, ‘We are the professors!’ And that was just the beginning. The band was not well-prepared musically, so I got involved in trying to teach them the music and memorize it. I was working at one end of the stadium and after a while, I noticed that parents were driving up. They soon started flashing the headlights of their cars. I thought that was odd, and Bob finally came over and he said, ‘Janzen are you going to spend the night here?’ I looked at my watch and said, ‘It’s just 7:50,’ and he said, ‘Janzen, your damn watch has stopped! It’s 9:30!’

The recruiting visits were the most important part of building the Arkansas band program, especially since they were in competition with Arkansas Tech, the best band in Arkansas, and their director, Gene Witherspoon, who was “Mr. Band.” To compete with Arkansas Tech and improve their chances of generating future Razorback band members, Robert Bright organized and started the University of Arkansas Summer Music Camp. The camp attracted many students from Arkansas, Texas, and Oklahoma. The camp was successful, but only after Bright eventually agreed to pay an additional portion of the camp’s revenue to the band directors of participating students. Each year, music camp students would cast votes to honor two outstanding music students. One year the two students who were voted to receive the honors were Pat Ellison and a young saxophone player from Hope, Arkansas with a passion for politics. His name was Bill Clinton.

Janzen also praised Chalon Ragsdale for his contributions to the development of the Razorback Band. Ragsdale joined the Arkansas band staff in the fall of 1975 and immediately added to the level of instruction. Excellent teachers with traditional values, Ragsdale and Janzen made the perfect team. Janzen spoke of his loyalty and how he and Ragsdale were always on the same page regarding their performance expectations and their approach to solving problems. Ragsdale was also valued for his ability to produce excellent marching arrangements and fine transcriptions for concert band.

Achieving Success

Janzen’s efforts paid off. By the 1975-76 school year, the Razorback Band was recognized as a quality university band, not only for the marching band but also for the size and quality of the concert band program and the wind studies department. build the concert band program and prepare his students for a profession in which new literature was being introduced at a rapidly increasing rate, Janzen added contemporary music and taught students about newer-sounding harmonies. For this type of music with this level of complexity of compositional sophistication to be accepted by their publics, Janzen also realized that they must provide some music education. One such performance that featured the Symphony for Band by Paul Hindemith, provided Janzen with the opportunity to introduce his audience to 20th-century compositional practices in a way that promoted understanding and enjoyment. In describing this performance, Janzen stated:

We performed a concert in the Arkansas Student Union ballroom where we performed the third movement of the Hindemith Symphony for Band. I’m sure that it was the most contemporary piece ever performed for the local audiences. Instead of a traditional concert performance, we presented a lecture that was designed to explain the structure of composition to the audience, many of whom had never experienced that level of compositional sophistication. We used sections of the band to demonstrate the various melodies in the final movement and how they were combined during the final moments. I knew that the Hindemith would not be received very well by the audience and I really loved the piece. I felt that they might appreciate the piece if they understood more about it.

Shortly after that performance, Janzen was contacted by David Whitwell in California. Janzen had recently received an invitation to perform at the 1976 National Educator’s Music Conference in Atlantic City, a national convention that would attract the leading figures in music education. This performance would be for the most prestigious performance audience for which an Arkansas music ensemble had ever performed. Whitwell was excited that Janzen would be playing the Hindemith Symphony because it had not been performed recently at the conference.

Following their performance at the 1976 National MENC convention in Atlantic City, invitations to other regional and national conventions began coming in on a routine basis. Janzen’s bands, along with Robert Bright’s brass choir, performed at numerous CBDNA conventions including those held in Kansas City, Wichita, KS, and Norman, OK. The University of Arkansas also hosted the convention in Fayetteville where the featured guest conductors were Willam Revelli and John Painter. The band would also take many tours that resulted in more talented students wanting to be part of the Razorback Band Program. Janzen credits his success to his students by stating:

When we performed at area schools– that kind of put some pressure on the band to raise the performance level because they were playing for kids their own age and they wanted to impress them.

The Key to Eldon Janzen’s Success

During our interviews, Eldon Janzen would continue redirecting the credit for his success to those around him. However, nearing the end of our final interview, Robert Bright turned to me and, as if read from a script, said:

Let me tell you why he did such a good job pulling this program together and I’ll just give you one example. It was the last band rehearsal the night before the game with Stanford in Little Rock. The game was scheduled ten days before the start of classes. So, he said to me, ‘Bright, pick up a yellow pad and follow me.’ He had told the band that there would be a military inspection in ranks. Well, that was unheard of. He said, ‘Just follow me and I’ll tell you what to write.’

So, we’re tooling through the band during the inspection and we come upon this guy who had long, bushy hair down to his waist. Janzen says, ‘Son, do you like playing in the Razorback Band?’ The student replied, ‘Oh yes sir!’ Eldon said to him, ‘well if you plan on being in the band, you will have your hair trimmed so that it doesn’t touch your shirt collar or your ears. And if you don’t get this done, there’s no reason for you to show up tomorrow.’ So, we get back to the band office I said, ‘Eldon, do you know who that was?’ He said, ‘No, and I don’t give a damn because this is the way it’s going to be.’ So, he set the posture right there that was the way it was going to be. When the kid showed up the next day, his hair was cut above his collar and didn’t touch his ears.

Three days later Janzen received a letter in the mail from David Mullins, the university president. The short note said, ‘Thank you, Eldon, for taking care of something that I’ve been trying to do for the last five years. Have a great season.’ The young man with the long, bushy hair was Mullins’ son.

Janzen’s belief in students and use of discipline made his bands successful. His leadership style also made Janzen a success. During his career, Eldon Janzen became an influential figure in the band world. He held the highest positions of leadership in some of the nation’s most prestigious professional music organizations, including serving as International President for the bandmaster’s fraternity, Phi Beta Mu. His dedication to students and the profession are surpassed only by his dedication to his family.

I am only one of the countless students who had the honor of having Eldon Janzen as a band director. Although Janzen is no longer active as a conductor, his influence can still be seen in the lives of his children, Jana and Scott, and those whose lives he touched. But perhaps most important, was his method of teaching these qualities to his students. You could hear it in everything he said and see it in everything he did.

Whether or not he realized it at the time, Eldon Janzen’s influence on his students extended well beyond the band hall or the marching field. He inspired us to be better people. He did this, without fail, every day that he came to work. As we ended our interviews, Robert Bright added:

You don’t build a band program, a family, or anything unless you have discipline—personal discipline. Eldon Janzen instilled in all of us the belief that we represented the state of Arkansas, and that means we needed to show our very best.

Eldon Janzen’s Professional Vita

Eldon Janzen’s professional affiliations include American Bandmasters Association, Music Educators National Conference, College Band Directors National Association, Kappa Kappa Psi, Tau Beta Sigma, and Lions International. He served as President of Texas Bandmasters Association, President of Southwest Division of CBDNA, President of Arkansas Bandmasters Association, and President of Phi Beta Mu International. He was recognized for his contribution to music education by membership in the Arkansas Phi Beta Mu Hall of Fame, received the Phi Beta Mu International award for outstanding contribution to music, was named Life President of Arkansas Bandmasters Association, and was a recipient of the “Distinguished Service” citation by Kappa Kappa Psi. Mr. Janzen was inducted into the Phi Beta Mu International Bandmasters Hall of Fame in Chicago on December 8, 2008. The American Bandmasters Association maintains a collection consisting of programs, articles, correspondence, facsimile photographs, video (DVD), and recordings related to Janzen’s career. Janzen has frequently served as a clinician, guest conductor, and adjudicator throughout the United States and Canada. He organized the Arkansas Winds Community Concert Band and served as its first Conductor and Artistic Director. For many years, his textbook, Band Director’s Survival Guide, was widely used in instrumental methods courses throughout the country.