Organist, trombonist, and composer Gustav Holst was one of Britain’s most celebrated musicians. In addition to his famous pieces for band (the two suites and Hammersmith: Prelude and Scherzo, Op. 52) he also composed operas, ballets, symphonies, songs, and chamber music. He is especially well-known as the composer of the “astrological” orchestral suite The Planets (1916). The First Suite inE-flat was composed in 1909 and premiered by the Royal Military School of Music Band in 1920. The appearance of this composition marks the beginning of an era of original works for wind band. Conductor Frank Battisti maintains that The First Suite:

is regarded as the cornerstone of the wind band repertoire and is a first-rate piece in both content and craftsmanship. Excluding Sousa marches, it is probably the most frequently played composition in the wind band repertoire.

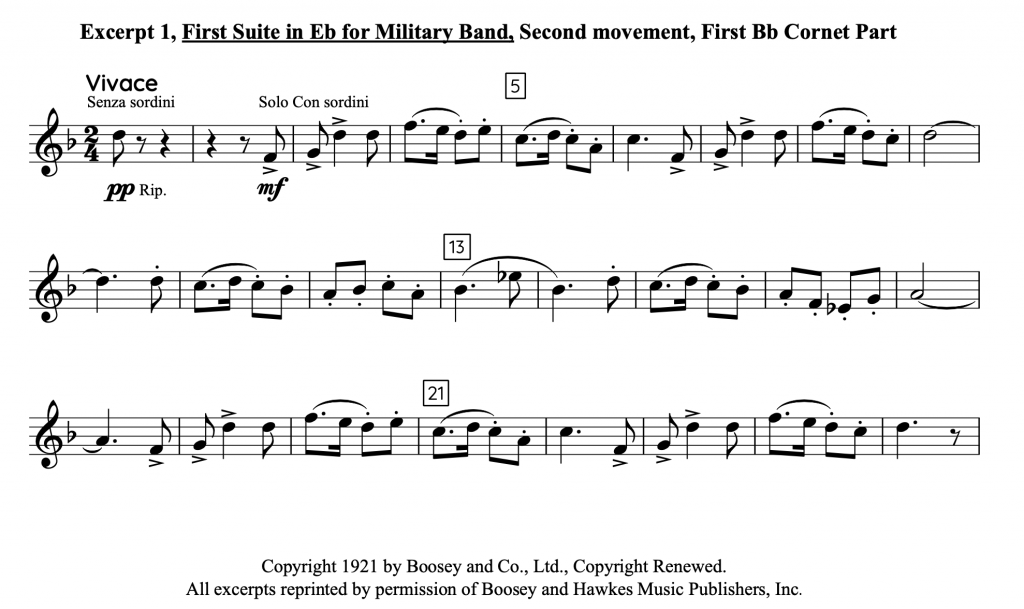

Like Grainger, Vaughan Williams, Bartok, and Kodaly, Holst was an enthusiastic collector of folksongs. The influence of folksong can be felt throughout the three-movement work and especially in Excerpt 1, which comes from the second movement, “Intermezzo.” Three editions published by Boosey and Hawkes are currently in popular use. The first was issued in 1921; the second, in 1948, was essentially a reprint of the 1921 edition but with increased instrumentation in order to conform to the size of American school bands. These full concert band versions contain many doublings among woodwinds and brass. Colin Matthews edited a new version, which was also published by Boosey and Hawkes in 1984. The orchestration in this edition is lighter, thus abiding more by the wind ensemble concept, with less emphasis on doublings. The melodic material and all the expression markings on the solo cornet part are the same in all editions. This discussion focuses on the original edition of 1921.

The tempo marked on the score for the Intermezzo is “Vivace.” The most common range of tempos displayed on various recordings is quarter-note = 138 to 142. While the rhythmical values are straightforward in Excerpt 1, the performer must keep the line moving forward and listen carefully to match with the steady stream of staccato eighth-notes played by the E-flat clarinets. This ostinato accompaniment in the clarinets keeps the subdivision slightly in the background, but constant.

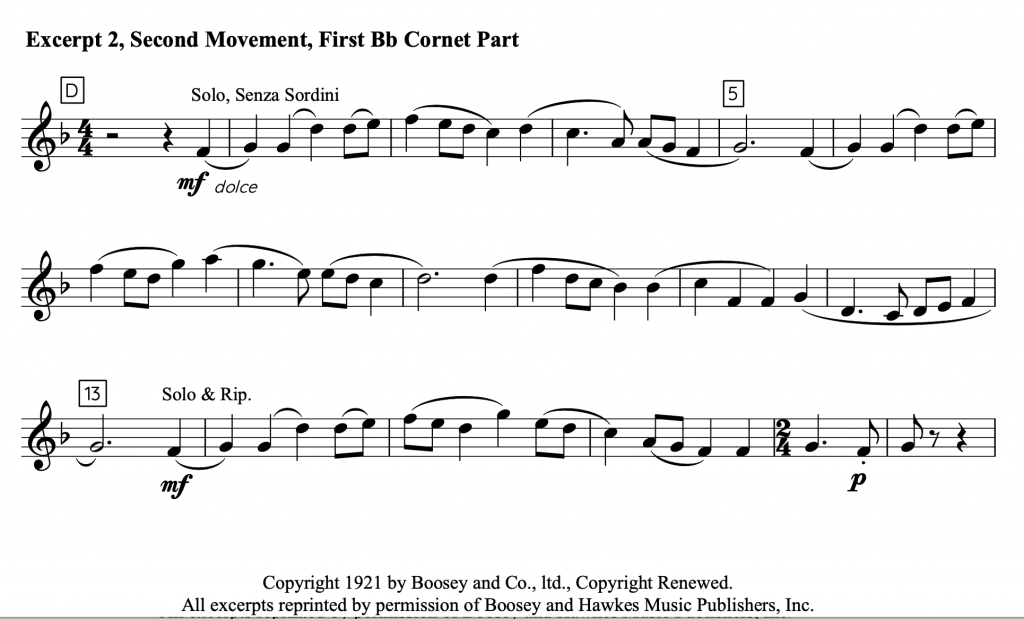

In Excerpt 2, the tempo can be the same as at the beginning but is sometimes slowed down by four to six beats per minute. The solo cornetist must again pay attention to the subdivision played by the clarinets. In this excerpt, however, it is the solo and second B-flat clarinets that perform a countermelody of running eighth-notes.

The music of Holst is written in the British band tradition, which makes use of cornets and trumpets with particular timbral functions assigned to each. In other words, Holst wants a cornet sound on particular parts and trumpet sounds in others for specific reasons. It is preferable, therefore, that this piece be performed on the instruments indicated in the score. The solos in the Intermezzo are from the solo B-flat cornet part. The mute for the second movement should be a straight mute. Most performers in the United States seem to prefer the metal mute, but this is largely up to the wishes of the conductor and performer.

An intermezzo is defined as “a middle movement or section of a larger work, usually lighter in character than its surroundings.” “Chaconne,” the first movement of this suite, is slow and serious. The cheerful nature of the second movement, true to the above definition, functions as a release of tension. Excerpt 1 is played in unison by the solo cornet, oboe, and solo clarinet. All performers must listen intently to one another on matters of pitch and phrasing. The metal straight mute tends to make a brass player’s pitch go sharp. It is helpful, logistically, if there is an assistant solo cornetist to play the first note of the movement which is “senza sordini,” thus allowing the soloist to rest and just play the solo. Since this note is doubled by the trumpets, this may not be necessary. Whether for this solo or in other repertoire, however, this type of part sharing allows the soloist to rest on the first note and to be ready with the muted instrument without worrying about making a quick mute insertion.

It is curious that Holst would double the material in Excerpt 1 in so many instruments and call it a “solo.” Frederick Fennell offers a possible answer:

. . . is the muted cornet solo an intentional double or is it a back-up in absence of the oboe? I am convinced of the latter: Holst was probably observing an ancient British army band security measure—scoring an important part for a reliable instrument in case of rain, when delicate instruments such as the oboe would have to be packed away in their cases. Remembering that British bands, then and now, are principally outdoor groups and that they rarely appear with more players than in Holst’s original instrumentation, one can and should make appropriate judgments within artistic conscience toward our customarily larger indoor groups.

Fennell’s reasoning deserves serious consideration, but all performances in the recording survey, and indeed, all those participated in by this writer have used the cornet or trumpet for this solo.

Breaths can be taken in the tenth and eighteenth measures, cutting off the dotted quarter on beat two. Accents must be slightly exaggerated at the beginning of the phrases, and the staccato notes must be light and not extremely separated. The mf dynamic marking is accurate whether performing in an ensemble or alone in an audition. A solid articulation such as “ta,” “tu,” or “tee” should be employed.

Excerpt 2 is doubled by the E-flat alto clarinet in the full concert band score and by the euphonium in the Matthews edition. The alto clarinet and euphonium parts are sometimes omitted, making this a true cornet solo. Nevertheless, the conductor will decide upon the desired sonority. The marking “Solo & Rip.” at measure 13 means solo and ripieno, or solo and doubled parts. This lyrical solo, marked “dolce,” should be played with expression even at the quick tempo and display a sense of direction. The vibrato and dynamic levels should ally themselves closely with the direction of the melody, gaining intensity as the line peaks at measures 7 and 15 and relaxing when the melody moves downward. The overall dynamic for the excerpt is mf, with the high points of the phrases being played at about f. Phrases should be marked by breaths after the dotted half-notes in measures 5, 9, and 13.

Trouble spots in terms of intonation are the G and A in measure 7, which are usually quite sharp and require humoring downward, and the D in measure 9, which is flat and needs to be raised slightly. The flatness of D and the sharpness of G in measure 15 can be problematic, since these two notes are next to each other in the melody.8

1Frank Battisti, The Twentieth Century American Wind Band/Ensemble: History, Development and Literature (Ft. Lauderdale: Meredith Music Publications, 1995), p. 3.

2There are no known recordings of the composer conducting this piece. His daughter, Imogen Holst, conducted this movement at quarter-note = 140 for the opening statement and slowed to quarter-note = 134 for Excerpt Number 2 (see Gustav Holst: The Complete Works for Military and Brass Band, The Central Band of the Royal Air Force, Imogen Holst, Conductor, CLP 3507, EMI 1966).

3Three of the four British bands in the listening survey used cornets to perform the solos in this composition.

4Randel, ed., The New Harvard Dictionary of Music, p. 398.

5Frederick Fennell, “Basic Band Repertory: Holst Suite in E-flat” The Instrumentalist 30 (April 1975) : 31.

6Randel, p. 709.

7Some British performers use a constant, fast, nervous-sounding vibrato. This is an esthetic preference and is prevalent among British brass bands. The use of this type of vibrato is not widespread in the United States, where performers tend to prefer a slower vibrato and use it more sparingly.8Note that the measure numbers appearing in these excerpts do not appear in the score are used for the purposes of this article only. Some British performers use a constant, fast, nervous-sounding vibrato. This is an esthetic preference and is prevalent among British brass bands. The use of this type of vibrato is not widespread in the United States, where performers tend to prefer a slower vibrato and use it more sparingly.

8Note that the measure numbers appearing in these excerpts do not appear in the score are used for the purposes of this article only.

(The above article originally appeared in the dissertation by Anthony B. Kirkland, An Annotated Guide to Excerpts for Trumpet and Cornet from the Wind Band Repertoire, University of Maryland, 1997.)